Sculpting Our Stories: Three Legendary Black Sculptors

We are honoring the artistic foremothers, sculptors and educators - Augusta Savage, Selma Burke and Elizabeth Catlett. While all of their profound legacies could not be encompassed in this post, we encourage you to do your own research, learn more about these women, and be inspired by their work.

Augusta Savage (1892 - 1962)

Augusta Savage stands with her sculptures “Susie Q” and “Truckin”, 1939. Photo via the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

“I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work.”

Spirited and talented sculptor Augusta Savage realized her love for clay as a child growing up in the brick-making town of Green Cove Springs, Florida. While her siblings were making mud pies she would be molding red clay into ducks and chickens. Unfortunately, her passion for creating was violently opposed by her minister father. This did not deter her from pursuing her dream of being an artist.

After studying at Cooper Union Augusta won the opportunity to study abroad at the Fontainebleau School of the Arts in Paris. When they discovered she was Black they rescinded the offer, claiming the Southern white women would feel uncomfortable. Despite the discrimination, Savage found her way to Paris years later to study, work, and exhibit. Short of funding throughout her career Savage would sculpt in plaster or clay, painting her pieces to resemble bronze.

Augusta Savage joyfully sculpts a fawn surrounded by rabbits.

During the Depression, she established the Harlem Community Arts Center at the 135th Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) and taught free art lessons. This was the beginning of her social activism. She helped found the Harlem Artists Guild that met at the 135th Library. Their mission was to promote youth education as a means out of poverty, racism and unemployment. It is noted she taught Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight. After spending time in Paris she returned to Harlem and opened her own school, Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts.

The 1939 New York World's Fair commissioned Savage. For two years, she created “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, a sixteen foot sculpture made of painted plaster. Depicting twelve Black singers as a harp being held by the hand of God, it was one of Savage’s greatest and most famous works. To Savage’s dismay, fair officials changed the work’s name to “The Harp”. Tragically, it was destroyed during the fair clean-up.

August Savage working on “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. Photo via New York Public Library.

After the World’s Fair, Savage was replaced at the Art Center, she sold no works at her solo show, and her Salon of Contemporary Negro Art shuddered after 3 months. Savage left New York City and the art world and settled in Saugerties, NY where she taught neighborhood children how to mold clay. Appallingly, of her 160 pieces 70 have been lost due to her inability to cast them in more durable materials.

As a Black woman artist navigating a white-male dominated world, Savage dealt with bouts of depression, but continued to remain true to her mission of depicting and celebrating Black life in her work. While monetary success was never her motive, creating work and inspiring young Black artists was her definition of success.

Selma Burke (1900 - 1995)

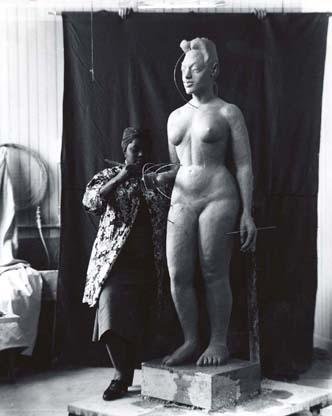

Selma Burke in her studio with her piece “Mother and Child”. Photo via Carnegie Museum of Art.

“I shaped my destiny early with the clay of North Carolina rivers.”

As a child in Mooresville, NC, Selma Burke spent her free time molding clay from the riverbeds. Her future was set in motion by an encouraging painter, her grandmother. After attending school in Washington D.C. she graduated from Winston-Salem State University. She received a nursing degree and found herself in Harlem in 1924. She taught at the Harlem Community Arts Center under the mentorship of Augusta Savage.

In 1933, Burke was awarded a Rosenwald Fellowship to study sculpture and travel through Europe. She studied in Vienna and Paris, where she was mentored by Aristide Maillol. After meeting Henri Matisse, he encouraged her to add size and volume to her work. Exploring human emotion, the body and familial relationships, Burke sculpted in wood, brass, alabaster and limestone. A self-proclaimed “people sculptor” she wanted her work to speak to a wide audience, not just artists and art collectors.

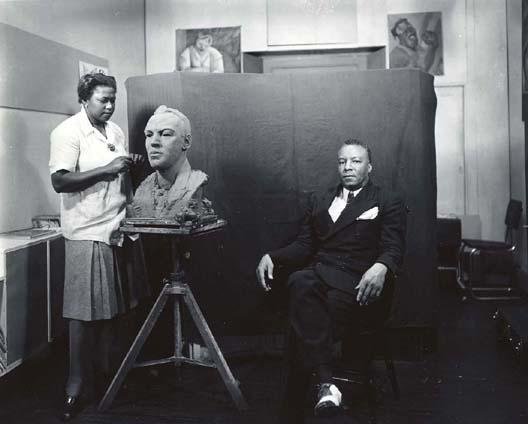

Selma Burke sculpting. Photo via Smithsonian American Art Museum

A true Renaissance woman, during World War II Burke returned to NYC and joined the Navy driving a truck in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Simultaneously she received a Master of Fine Arts from Columbia University. She opened the Selma Burke School of Sculpture. After getting married, Burke moved to an art community in New Hope, PA. An educator at heart she shaped young minds at Swarthmore College and the George School. Like Savage, Burke’s passion for teaching led her to opening the Selma Burke Art Center in PA. Her mission was to teach children the vibrancy of sculpture and learning through touch.

In 1944 Burke sculpted a bas relief of a young President Roosevelt. In 1946, commissioned by the US Mint, John Sinnock heavily adapted Burke’s work for the design of the dime. A crime as old as time - stealing the ideas and visions of Black folks, Burke did not receive credit for the work. We will forever recognize and acknowledge Selma Burke as the creator of the FDR profile on the dime - John Sinnock stole that sh*t.

Elizabeth Catlett (1915 - 2012)

Elizabeth Catlett teaching a sculpting workshop, 1970. Photo by Walter Neal via Fine Art America.

“Art is important only to the extent that it helps in the liberation of our people. ”

Similarly to Savage and Burke, sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett knew art was her life’s path. Born in Washington D.C Catlett absorbed the stories and realities of her mother and grandmother. These familial Black women’s narratives inspired her creative vision.

In 1931, Catlett attended Howard University where she studied art history, printmaking and painting. After teaching for two years in Durham, NC and advocating for Black teachers’ equal pay she attended graduate school at the University of Iowa. There her medium of interest shifted from painting to sculpture. Her mentor, Grant Wood encouraged her to choose subjects she was closely familiar with.

Elizabeth Catlett in her studio.

Catlett won the First Award in Sculpture at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago for her now lost piece “Negro Mother and Child”. From 1940 - 1942 she taught art and art history at Dillard University in New Orleans. Going beyond classroom teaching, Catlett transformed her students’ perspectives on art - including bringing them to the segregated Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art).

She spent the summer of 1941 in Chicago, studying ceramics at the Art Institute and lithography at the South Side Community Art Center. She was surrounded by a community of artists and activists creating work for social change. Continuing her artistic journey she moved to New York City, where she inspired and was inspired by her students at the George Washington Carver People’s School.

Upon receiving a Rosenwald Fellowship not once, but twice Catlett relocated to Mexico to work on her linocut series “The Negro Woman” later named “The Black Woman”. This series depicted the realities, triumphs and tribulations of every day Black women while honoring them and historical Black heroines.

During the Cold War’s government attacks on artists, intellectuals and activists, Catlett decided to make her permanent home in Mexico. She observed the commonalities of working class Black and Mexican people, particularly mestizaje people with Indigenous, Spanish, and African ancestries. Her return to teaching and sculpture in 1955 was met with pushback from male colleagues. Unswayed by their misogynoir, she continued to inspire her students while creating work depicting Black women and children and advocating for justice for Black, Mexican, and other oppressed peoples. Catlett moved through her life with generosity and kindness creating work, raising awareness of injustices and abuses of power, and honoring the beauty of Black life.